The Passion of Jesus Told through Music

The Passion of Jesus Told through Music

The Georgian church chanting tradition has long gained international recognition for its unique qualities and ancient origins and has contributed many wonderful and unforgettable hymns to the treasury of world music. The Shekhvet’iliani hymns, which are included in the reading of twelve Gospel passages during the Good Friday service, hold a particularly prominent place among them. The Shevkhet’iliani cycle is monumental, containing seventy hymns. The verses, following the Gospel chronology, describe Jesus’s passion and crucifixion, beginning with the Last Supper and ending with the burial of Christ. The hymns were a tenth-century creation, and neither the author nor the composer are known. The texts were translated from Greek into Georgian around the same time by renowned hymnographers of the Mount Athos monastery in Greece, Saints Ekvtime Mtats’mindeli and Giorgi Mtats’mindeli. The latter’s translation is the one used today.

The Shekhvet'iliani musical cycle, dedicated to the Passion of Jesus Christ, is unique in the way it combines a variety of hymns or irmoi in different modes with chants that typically have other liturgical functions. There are chant melodies, for instance, from various liturgical collections—markhvani (fasting hymns), p’araklit’oni (paraklesis or supplicatory hymns), and tveni (calendar hymns). There are also chant melodies typically belonging to the high holidays—Transfiguration, Epiphany, Nativity, and the Dormition of the Virgin—as well as hymns from ritual processions, funeral rites, and other chant compositions (specifically certain tones belonging to chant forms known as troparion, dasdebeli, and tropar-dasdebeli). Such a wide range of melodic sources for a hymn cycle is quite unusual and deserves special attention. In this regard, there is nothing analogous to the Shekhvet’iliani in liturgical practice.

The unusual musical composition of the cycle is explained by Saint Giorgi Mtats’mindeli in a manuscript held in the library of the Iviron Monastery at Mount Athos, known as Ath. 38. In the inscription attached to the Shekhvet’iliani cycle, he notes that he did not follow the Greek tradition, which required the creation of original hymns, but rather set the Shekhvet’iliani texts to the musical structure of hymns familiar to Georgians from ancient times. The reason he gives for this choice is that that he was unable to find anyone on Mount Athos who was willing to learn new hymns. Therefore, to ensure that they made their way back to Georgia, Giorgi Mtats’mindeli had the Shekhvet’iliani cycle performed using melodies that were well known to the singers, which he marked in the text as dedani-hangi (literally, “original tune”). Dedani-hangi indicates a kind of template, a pattern according to which this or that hymn may be sung.Thus, throughout the manuscript of the Shekhvet’ili cycle, one sees written in red ink the incipit, or opening words, of other hymns. These other hymns, which come from various parts of the chant tradition, thus provide the musical structure for the Shekhvet’ili texts. This is how so many different modes and melodies came together in one hymn cycle. In addition, the above-mentioned inscription is extremely interesting in that it contains valuable evidence for the independence of Georgian church chanting from Greek practice and is another source testifying to Georgian chants having been sung in Georgian since the eighth century (Fig. 1).

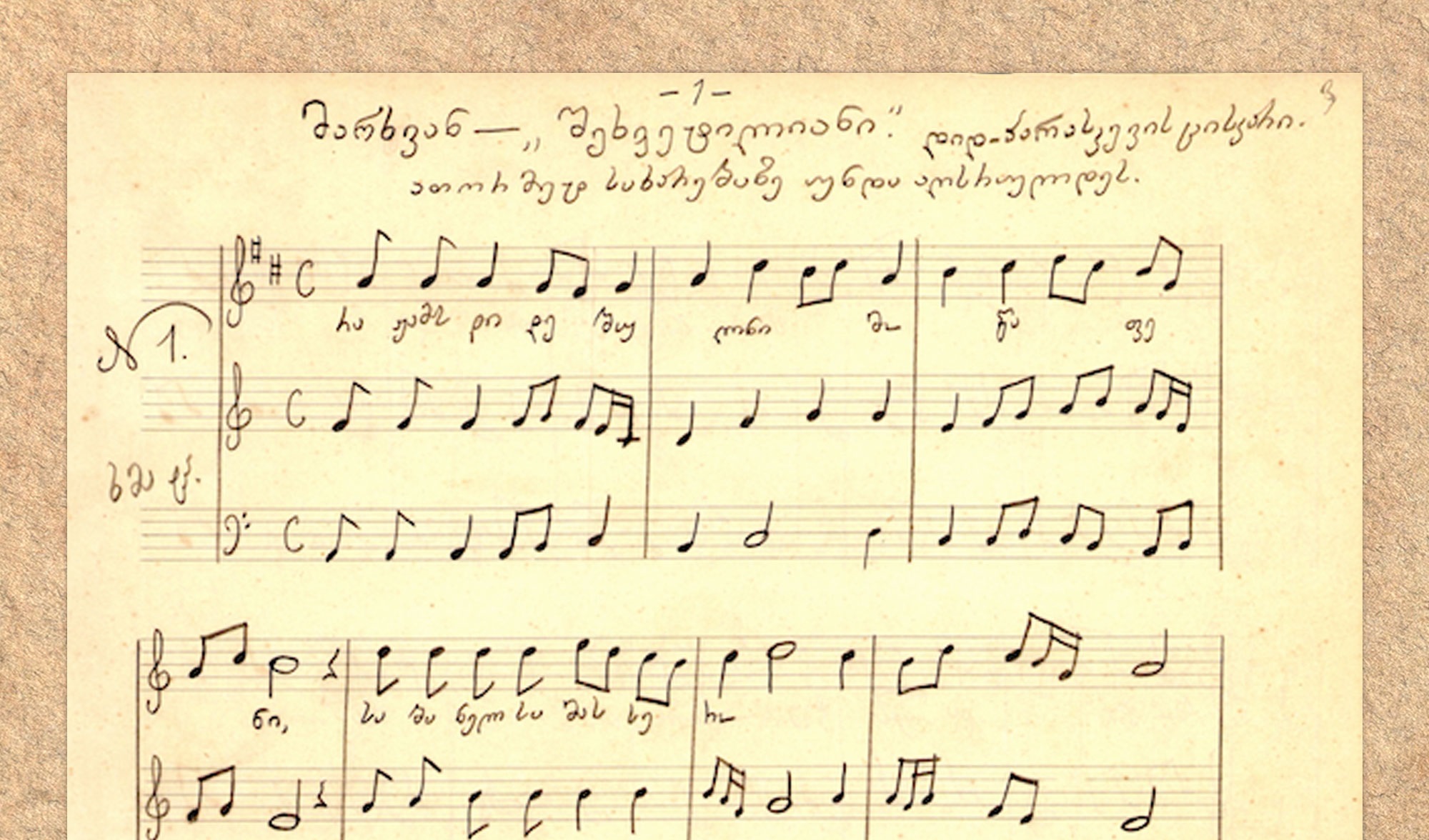

Like the majority of Georgian chants, the hymns of Shekhvet’iliani were transcribed into Western notation at the turn of the twentieth century. Two manuscripts are in existence: one from the musical collection of St. Ekvtime Kereselidze, preserved in the Kekelidze National Manuscript Center (manuscript Q 686), and the other a manuscript by the deacon Razhden Khundadze (# 2128) preserved in the archives of the State Folklore Center.

Pilimon Koridze, an opera singer later canonized for his role in preserving Georgian chant, recorded the upper voice-part of the Shekhvet’iliani cycle from Anton and Davit Dumbadze (Anton’s son, an archpriest), who were famous chanters from Guria. Koridze himself then tried to add the middle voice-part, but he was not able to finish, only completing twenty-seven of the seventy hymns in the cycle. The rest of the hymns in Koridze’s original manuscript were arranged in three voices by Razhden Khundadze. Ekvtime Kereselidze, in turn, made a copy of Khundadze's manuscript.

What does the Shekhvet’iliani cycle tell us about itself, or what did the author mean by calling it that? The term Shekhvet’iliani has several meanings. In musicological literature, it was first discussed by Manana Khvtisiashvili, whose interpretation connected it with the Passion of Jesus and the crucifixion. She called the musical cycle itself the “Georgian Passion.” (1) Indeed, Shekhvet’iliani is defined in the dictionary of the old Georgian language as a term expressing the suffering and sorrow of the saints. (2) This is confirmed by the hagiographical and hymnographical sources, where the word khvet’a, which now refers to “shoveling” or “raking” is mentioned in the context of the cruel suffering of the martyrs. The term Shekhvet’iliani has other meanings as well. It has been found in secular literature since the eighteenth century in reference to a type of collection in which works by different authors with varied content are compiled, i.e., an almanac or anthology containing pieces from different epochs, styles, and authors. Three Shekhvet’iliani collections (A-999, A-858, and A-860 in the Kekelidze National Manuscript Center), compiled in 1772-1779 by Nikoloz Chachikashvili, famous as a copyist of Shota Rustaveli’s medieval epic The Knight in the Panther’s Skin,are clear examples of this. These collections gathered together various works, including Rustaveli’s poem, other Georgian texts from the medieval period like the Zakariani, Saamiani, and Rost’omiani (all translations or adaptations of the Persian poet Ferdawsi’s Shahname), the Amirandarejaniani and continuations of Rustaveli’s work like the Omainiani.

Shekhvet’ili is also found as a toponym in Georgia. As the name of a village in Kakheti, it is a sign that the population settled here came from different regions. The administrative unit of the Ilto Gorge in the Kvemo Kartli region in Eastern Georgia, whose population largely migrated from the mountainous region of Pshavi , is also called “Shekhvet’ila” (Fig. 4).

As we can see, the thematic content of the Shekhvet’iliani cycle related to the Passion of Jesus is consistent with the first meaning of the term, which denotes torture and suffering. The second meaning, on the other hand, emphasizes the composition of the cycle as a combination of diverse modes and hymns with different liturgical functions. As mentioned above, no other musical cycle in liturgical practice has such a large number and wide variety of hymn melodies. Although we do not know who wrote the text or music of the Shekhvet’iliani cycle, nor who gave it its name, the name has come to refer simultaneously to the Passion of Jesus and to the collection’s musical diversity.

Supplement: Audio recording of the hymn “Satsnobelni Chvenni”, tone 5. First dasdebeli (troparion) or stanza of the Shekhvet’iliani cycle. The hymn was recorded in the “Georgian Chant” studio of the Giorgi Mtats’mindeli University of Chant in Tbilisi, with the participation of students from that institution.

References

- Khvtisiashvili, Manana. 1997. “Kartuli p’asionis k’vlevis p’irveli shedegebi” (Preliminary results of research on the Georgian passion). In Musik’ismtsodneobis sak’itkhebi (Questions of musicology). Tbilisi: V. Sarajishvili State Conservatoire.

- Abuladze, Ilia. 1973. Dzveli kartuli enis leksik’oni (Dictionary of the Old Georgian language). Tbilisi: Metsniereba, s.v. “khuet’a,” 564.